I envy snakes.

I envy snakes.

True, anyone can live their life in a constant cycle of tiny deaths and rebirths, but their biology provides them with an evocative visual metaphor for it (which I hope they appreciate). I am obsessed with transformation to an almost unhealthy degree.

I’ve often lamented growing up in a culture where the commonly accepted rites of passage are superficial (prom), boring (graduation ceremonies), rapidly becoming irrelevant (owning houses and cars), or some combination of all three. For the sake of feeling like a cohesive person, I’ve created my own rites and rituals by and for myself, but they don’t make much sense outside of my personal context and don’t place me within a wider community the way a more common and understood ritual, like a baptism, would.

But sacred tattoos are physical, things that can be looked at and touched, and are understandable to everyone in that sense. They are a literal transformation; a body with a tattoo is not the same as the unmarked body that came before it. This cycle of change and renewal has been crucial for much of my life.1

Inspiration for a sacred tattoo

I did my research of course, lots of it. I looked at tattoo traditions around the world. I began with traditional tribal practices, looking at Polynesian, African, and Native American traditions. I saw many and varied reasons for tattoos: for beauty, as a rite of passage, to attract or repel certain spirits, for fertility and hunting prowess, to symbolize battles and fallen enemies, and so on. I researched Western subcultures that use tattoos, particularly sailor and prison tattoos. It was a different dictionary of symbols, but many of the same ideas — marking social status, deeds done, and protective and talismanic symbols.

I was beyond fascinated with what I learned about tattooing cultures, but felt the need to keep some distance. To borrow too heavily from any of them, to place myself within another culture, would negate the idea of expressing my own context (and also be horribly appropriative). At that point, I knew what I needed to do. Altering the body permanently in this way would give me what I was after: a sense of physical and spiritual transformation, an ordeal (with pain, an altered state of consciousness), and a physical mark that can can be recognized by others.

Chrysalitic withdrawal

My final tattoo design was the result of sketching and deep thinking on-and-off for a year. My first instinct was to create something specific to my hardships and how I overcame them, a sort of permanent “fuck you, I’m still alive!” But then I realized that, much like the hipster who rabidly rejects everything mainstream, I would be defining myself in negative terms; in terms of what I am not as opposed to what I am. So I set about creating something very “me,” and also magically charged, so it could be empowering on multiple levels. A lot of that process has been lost, sketched out on napkins and old work schedules that have since scattered to the four winds, but everything came together quickly after a moment of cohesion.

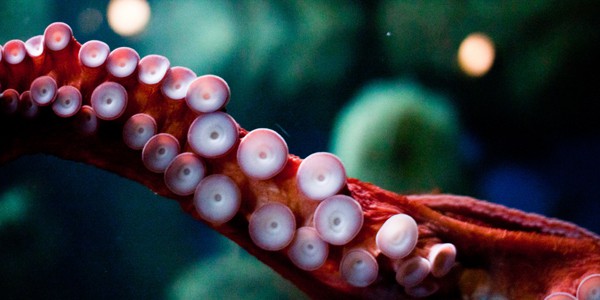

My final design started its life as a long, thin, tattoo down the spine. It would have had seven orbs with planetary symbols (the chakras) with tentacles coiled around them, holding them up. I have a tendency to complicate when I should simplify, and I recognised that happening, so I pared back.

I knew the tentacles would stay. They were in every iteration. They are a powerful personal symbol of my fundamentally non-human nature (long story short, I’m a reincarnated alien), where I came from, and where I am going. The eye was important as well; on my earlier design, the crown chakra was represented by an eye with the Sigil of the Gateway — an important symbol in the Cthulhu Mythos — in the centre. In the new context, the sigil would have been over-complicated and almost redundant, so I replaced it with a spiral, indicating cyclical nature and also evoking both a portal and a black hole. By that reasoning I made the new design radial rather than linear.

So there was the seed of the final image: a spiral-eye with four tentacles emanating from it. I needed an aspect that showed life and physicality: the soft, sweet, pleasurable things about being on this planet and in this body. Flower petals came to mind quite organically. Four of them, blooming out between coiling tentacles. Between each petal and tentacle is a black spike shape, eight in all. They are deliberately vague, meant to evoke many things: spider legs, stars, knives, needles, tears in reality, generally things that make me happy. After another step back, I realized I had worked in multiples of four, which speaks to me of solidity, calmness, and grounding; I had made a compass. And my shards of inky black void totalled eight which, turned on its side, is infinite.

I also kept the colours from the chakras. The petals fade from red to yellow like a flame. The tentacles, of course, are green. The area surrounding the eye is purple and the eye itself graduates from blue to indigo. I placed it on my back, between my shoulder blades, because that’s where most of my phantom tentacle sensations emanate from. I subconsciously placed the eye — the ex-crown chakra — over my heart chakra. There’s something delightfully sentimental about that.

Underneath that packed image are the words “I spring eternal.” I’ve adopted those words as a magical motto of sorts, and having them etched permanently into my skin feels very correct. It has several meanings, most of which boil down to the fact that I am extremely hard to kill.

I’ve lived many times, more than I can remember, but I recall enough to know I’ve died unpleasantly more than once, that I’ve wanted to give up and forget my journey, and that I haven’t. I spring eternal.

People have tried to make me feel small, devalue my gifts, and take my power, but it never lasts. I spring eternal.

And I know that whatever comes, I can find a way through it. I spring eternal.

Feeling those words sink into my skin, following the needle over each letter, would be sublime.

Threshold guardian

When it came time to find an artist, Rowan Kimsey of Bless This Mess Tattoo Co. was recommended to me. When Rowan was 22 she was offered an internship with a famous tattoo artist, but declined. She went on to be an illustrator, drawing for publications such as Sage Woman and PanGaia, but she felt isolated, staying in her studio all day and communicating over the Internet. She’d been told many times that her style was good for tattoos, and she wanted to form connections, and so she made up her mind to pursue tattooing and spent two years talking her teacher into accepting her as a student. She and her teacher share a powerful bond, and she considers herself the heir of a spiritual lineage as much as an artistic one.

Rowan’s own tattoos have been deeply transformative. Her first came towards the end of her apprenticeship and as she was going through a divorce: a crow on her back, a guardian to look out behind her. She believes very strongly in the power of symbols, and often works with her clients to make sure they’re saying what they want to say.

When I asked Rowan about various tattoo traditions around the world and what left an impression on her, she told me that what stood out to her was that there is a tattoo tradition virtually everywhere. The impulse to express something invisible in a physical way is universal. Even during times when tattoos were less acceptable, people found other ways to express this impulse, to bring their bodies in line with some internal ideal. She cites things like corsets and high heels, which eventually change the shape of the body, as evidence of this. She believes tattooing has become demystified in the last 20 years or so because we are more open as a culture; people are more open about their lives and accustomed to being on display.

Rowan described to me the state of surrender that happens during a tattoo. This can happen whether a person is spiritual or not; its a state of vulnerability and acceptance, being able to let go and allow the change to happen. She can feel when that surrender happens; the tattoo becomes nearly effortless. And people often talk to her in this state about the meaning of their art, creating a dynamic of trust and vulnerability. She often feels like a priestess in a confessional, and is honoured to be the “keeper of a thousand amazing stories.”

Transfiguration

When the day came for my tattoo, I went by myself. I wish I could say that was a conscious choice, but it never even occurred to me that I could have asked someone to come with me until after the fact. I’m very grateful for it; I wouldn’t have been able to access the state of mind that I did had someone been there talking to me or holding my hand.

Rowan and I both understand the pain and bleeding as part of the ritual, a blood sacrifice that allows that state of surrender to happen, and for change to occur. I was intrigued by how different people handle the pain: some, like me, slide into an altered state of consciousness, some cry, some distract themselves, and some become angry (Rowan has a regular client who curses her out through the entire process). Some tribal societies view the pain of tattooing as atonement, or a vehicle to send a prayer. For me, it was more like the latter; not a punishment, but a means to an end to achieve a transformative state.

The pain was constantly evolving; sometimes pinching, sometimes burning, sometimes like an electric shock. And I felt very accepting of all these sensations. I had no urge to judge or quantify them. They were there, then they changed, then they were gone. I was acutely aware of each moment and how temporary it was. After the endorphins kicked in it was almost a game, guessing which part of the design I was on and meditating on its meaning.

In the end, the whole experience felt shorter, hurt less, and healed faster than I thought it would. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the healing process of a tattoo involves a layer of dead skin flaking off; a literal shedding. I almost want to tattoo my entire body just to make the effect complete. (I briefly considered trying to sell the multicoloured flakes as organic confetti, but then I remembered I live in Portland and someone might actually take me up on that.) And even now that the tattoo is fully healed, the skin still feels wonderfully new. I suspect that sensation is permanent.

And I am part of a wider community now – people with sacred tattoos. Its a wide, nebulous, and very diverse community, just the way I like them.

I feel new, as though part of me is only a month old.

I feel strong for having endured the pain.

And I feel connected; people see my tattoo, ask what it means, and I have an answer for them. I created an affirming and empowering image of myself. And in the end, some of the “fuck you” sentiment remains, but its a kinder, gentler “fuck you” that smiles and shakes its head and gets back to living well.

And springing eternally.

Further reading

Lars Krutak. “Shamanic Skin: The Art of Magical Tattoos.” larskrutak.com. 2009

Reverend Barb. “Tattoos: A Spiritual Imprint.” reverendbarb.com

Jacob D. Meyers. “Holy Ink: The Spirituality of Tattoos.” The Huffington Post. 2012

Phyllis Hanlon. “The Deeper Meaning of Tattoos.” Spirituality and Health.

- See also, “Pomegranates and trauma: Delving into the Underworld. [↩]