John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochian Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World, by Jason Louv

John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochian Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World, by Jason Louv

Inner Traditions, 9781620555897, 560 pp., 2018

Jason Louv‘s new book, John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochain Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World, is a departure from his previous works. His other titles have pride of place in my occult book collection, and I’m a fan of his other work also, such as the Ultraculture blog and podcast, and his online magick school magick.me. He has a way of making really complex ideas accessible and has been instrumental in introducing modern magick including esotericism, Western hermetic magick, ceremonial and chaos magick to a younger audience.

In John Dee and the Empire of Angels, Louv has taken on a huge project — providing a historical account of the life and work of John Dee — which involved explication of a great deal of Elizabethan history, the bloodshed and tumult of the reformation, and of course an enormous amount of political intrigue. Dr. John Dee was a scientist and occultist who lived from 1527 to 1608. During his lifetime he developed what became the scientific method we use today. In his capacity as a respected occultist, he became a court advisor to Queen Elizabeth, using his skills of astrology, prophecy and occult counsel to advise her regarding political matters.

Louv’s approach to the topic is interesting. He tries to reconcile the two traditional narratives that have emerged around John Dee’s life and work, melding together the story of the visionary astronomer, mathematician and scientist with the tale of the occultist who learned pre-Edenic angelic language via scrying sessions conducted with an alcoholic miscreant, Edward Kelley. Louv’s approach is staid and scholarly, and he is able to methodically synthesize enormous amounts of historical, political and occult knowledge for a diverse readership.

In his occult work, John Dee famously developed a system for communication with angels which provided him access to celestial counsel regarding spiritual, intellectual and political matters. The system he developed in collaboration with Edward Kelley (1555-1597) allowed them to access what came to be known as the Enochian (angelic) languages, which came to them directly from the angels themselves. Communication with angels was considered a relatively legitimate pursuit in the middle ages, and Louv does an amazing job of setting the stage for these experiments, providing the necessary historical and cultural context regarding how “angelology,” a Dionysian system that describes a sort of ranking and file of angels, was (and remains!) central to Christian mysticism.

Louv discusses John Dee’s work with Edward Kelley, including theories as to how the men worked together and how credulous both were in their symbiotic working relationship, including specifics regarding how the pair communicated with angels and what they learned. Louv dissects Dee and Kelley’s spirit diaries, where they recorded their techniques and resulting angelic communications. The material is often presented as either a miraculous achievement, or a sort of parlour game that achieved significance in part due to the dedication and fervent belief of its creators. It’s interesting to consider this idea, and Louv acknowledges that the spirit diaries created by Dee and Kelley occupy an odd liminal space in occult circles, and also in history. Were their results fictitious? There seems little doubt that they were real enough to John Dee and Edward Kelley.

John Dee and the Empire of Angels is organized into three sections: the first concerning Dee’s early years and scholarship at Cambridge, through his work as a mathematician and astronomer and leading up to the early 1580s when his collaboration with Edward Kelley and the angelic investigations began. Louv emphasizes that had Dee not begun his occult explorations, his main legacy would have been his scientific work which Louv places at a calibre on par with Copernicus and Newton. The second section of the book concerns the angelic work. Finally, the third considers the impact of Dee’s work on the modern world, acknowledging that the angelic work of Dee continues to impact significant avenue of occult study, hundreds of years after his death.

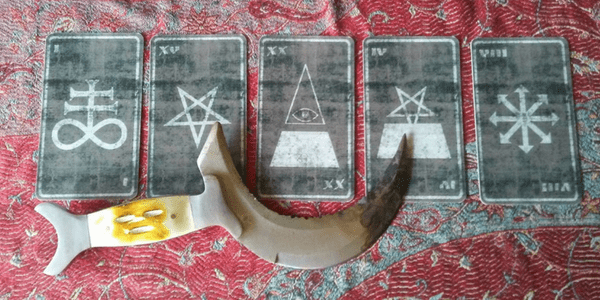

I found the second section, concerning the angelic conversations themselves, difficult to navigate. The spirit diaries that Louv is trying to make accessible here are pretty difficult to penetrate. I think Louv did an admirable job in documenting how the angelic conversations happened and the practicalities whereby Dee and Kelley developed the Enochian table. However, wading through accounts of angelic communication that involved a complex system of tables representing 644 angelic characters, 30 aethyrs and 91 governors grouped to represent 91 earthly locations and 49 angelic calls to interact with watchtowers and aethyrs, I wasn’t able to find a way to make this coherent enough to be useful. Thankfully, Louv does provide historical context in this middle portion of the book, so at least the reader feels bound to Dee and Kelley’s interpretations of the angelic communications and can follow the activities that resulted from the work during the 10 years when the pair were absorbed in the angelic pursuits.

The last section is probably my favourite. Louv manages to place the work of John Dee in a broader cultural context, demonstrating how his work impacted and contributed to the dawn of Rosicrucianism, the work of Francis Bacon, and thereby the entire scientific method that we are familiar with today. Louv continues connecting the Dee dots via Freemasonry, the Golden Dawn, the Ordo Templi Orientis, Aleister Crowley and Thelema, right up to Jack Parsons and Anton LaVey. It’s wonderful scholarship and an exciting analysis that brings Dee into the 20th century in a convincing way. It’s also stimulating to see the ripple effect of Dee’s work, and to reflect on how influential his ideas were, especially considering how outlandish the claims of angelic communications seem today.

It’s also a nice looking book! At the back there are extensive notes, a full bibliography and an index that makes navigating this huge book a little easier. It’s not actually the size of the book that makes it a challenge (though it is 560 pages long), it’s the enormous scope of the work that makes it such a great read and a formidable accomplishment. It includes black and white photos throughout, depicting historical figures and also relevant artwork from antiquity. There’s a centre section with full colour plates — everything from images of the scrying crystal thought to be used by Dee and Kelley to Enochian tables and paintings by William Blake.

Louv’s John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochain Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World contributes something unique to historical occult literature without question. He writes clearly and authoritatively, and as mentioned he makes complex contexts legible to modern readers in a way that makes this book valuable to lay or occult readers alike. He was able to straddle reconciling Dee’s occult and scientific accomplishments admirably, and synthesized them to place Dee in a place of great honour in multiple histories: occult, socio-cultural and scientific.

Image Credit: John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I by Henry Gillard Glindoni