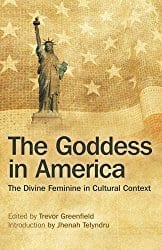

The Goddess in America: The Divine Feminine in Cultural Context, edited by Trevor Greenfield

The Goddess in America: The Divine Feminine in Cultural Context, edited by Trevor Greenfield

Moon Books, 978-1-78279-925-2, 194 pp., 2016

I sat down to write this review of The Goddess in America: The Divine Feminine in Cultural Context weeks ago yet, courtesy of the serendipitous web of time, I am writing it on the fourth of July, Independence Day in the United States. Many American eyes will be watching televised fireworks over the Statue of Liberty, the great feminine beacon — a representation of the Roman goddess Libertas — that presides over New York Harbor, surrounded on land and sea by the flag.

That is also the cover image on The Goddess in America, a collection of essays which seeks to illumine how goddess-affirming people in this “melting pot of nations” and “cauldron of cultures” have, and are coming into relationship, with Her. Modern American Pagans must navigate a tightrope of sorts in this regard: To honour the ancestors of the land, they must come to grips with a devastating history of colonialism and genocide against First Nations peoples, learning to engage while avoiding cultural appropriation. Or, they must forge entirely new methods of relationship based on ethnic ancestors from lands separated from them by oceans and time, or from images in popular culture that resemble the divine feminine.

The book is divided into four parts — “The Native Goddess,” “The Migrant Goddess,” “The Relational Goddess,” and “The Contemporary Goddess” — with several essays in each.

“The Native Goddess” discusses how matriarchal indigenous cultures influence the Goddess movement, with essays devoted to the Cherokee, Hopi, and Maya. “The Migrant Goddess” examines non-appropriative Pagan practice, and describes Irish, African and Creole, and Hebrew goddesses. “The Relational Goddess” juxtaposes the concept of Goddess with what could be considered five archetypes: the Feminist, the Shaman, the Christian, the Psychologist, and the Witch. Lastly, “The Contemporary Goddess” describes how She is defined in the context of modern life, such as in pop culture, the Reclaiming and Goth communities, and in the roles of women in today’s America.

Of the many essays in this book, two stood out for me — no doubt because of my own background and path of practice. The first is “The American Dilemma: Engaging in Non-Appropriative Pagan Practice,” by Jhenah Telyndru, the founder of the Sisterhood of Avalon.1 Telyndru briefly discusses the roadblocks to Pagans desiring to follow a particular tradition: being too far removed from their culture of origin; not having a clear path to any one practice, if of multicultural descent; or not having a way to connect with the ancestors of the land they live on without cultural appropriation — and, quite possibly, being descended from those very Americans who persecuted First Nations people.

As an entry point that counters some of these challenges, Telyndru offers a “philosophy of engagement”: listen, engage in culture, emulate practice, and connect with the land.2 She elaborates on each of these points, and concludes by saying that “one’s blood or DNA, in my opinion, is less important than how one actively engages with the culture, tradition, and societal mores of the nations from which one’s Goddesses arise. In the end, one’s spiritual homeland is found nowhere but within one’s own heart.”3

“A Dream of the Wise Woman’s Comeback: Priestessing for Goddess in Today’s America,” by Kate Brunner, a member of the Sisterhood of Avalon, opens with a dream sequence describing a modern wise woman. She is one who has,

a commitment to work in the world as a healer, protector, advocate, ritualist of the everyday, and conduit for community connection. Hers is not the way of high magic. She is no High Priestess with a lineage of formal instruction and initiation. Hers is the way of stick and stone, blossom and bone. Hers is the way of radical grace in service to whomever Goddess puts in her path; of grounded optimism in a time and nation that desperately craves creative solutions. She is the grass and the roots. And she is rising.4

Brunner then describes each of the five aspects of the wise woman, with questions, examples, and suggestions for those who may be called to service in that particular way.

The Goddess in America offers a window into the richness and complexity of the divine feminine in today’s America. As in America itself, its diversity of pathways contains its strengths and its challenges, and ultimately its grace. Telyndru writes in the introduction that Lady Liberty is “in many ways a psychopomp” who “guided seekers through the gateway to the new world,” just as the Goddess holds an undeniable light which guide those who seek Her.5 Telyndru then offers a closing benediction:

May those who honor the Divine Feminine in all of her manifestations and guises here in America pick up the torch of the Lady of Liberty, our beautiful and powerful national Goddess, and recommit to the promise of peace, safety, and freedom her flame represents.6

So mote it be!