There’s a certain something about occult documentaries made in the 1970s. Maybe it’s the style — the colours and tones are rich and vibrant and the wardrobe has a certain vintage feel that I love. Or maybe it’s the content? Interviews with well-respected founders of contemporary traditions and footage of rituals conducted in spaces that I can only dream of visiting give me access to a time and place that no longer exists.

There’s a certain something about occult documentaries made in the 1970s. Maybe it’s the style — the colours and tones are rich and vibrant and the wardrobe has a certain vintage feel that I love. Or maybe it’s the content? Interviews with well-respected founders of contemporary traditions and footage of rituals conducted in spaces that I can only dream of visiting give me access to a time and place that no longer exists.

The moods in these films shift back and forth from serious to slightly laughable; in one segment we get an honest and thoughtful sound bite from a well respected occult talking head, and in the next, a scene that is just a little too stereotypical; a naked woman grooving on an altar, middle aged English folk running skyclad in a circle, and lots and lots of black velvet attire.

In some cases, these films were produced as gawkfests for the average television audience, and the slight campiness they play with certainly is captivating. But, watching closely, we can see how they were also carefully calculated engagements with mainstream media: ways to be captured on film, preserved for all time, and reach out to the wider public to let them know that, yes, we exist.

Today, thanks to digital technologies, these documentaries are seeing a life well-past the decay of the original film, and reaching audiences much wider than originally intended (all of these films are — or were — accessible on through the Internet today). These films seem, to me at least, to beg the question of authorship; when in front of the camera — or put in any kind of spotlight — just who is leading the ritual?

The Power of the Witch (1971)

BBC’s The Power of the Witch was originally aired on the BBC in 1971 and is structured as a sort of expose of the British revival of witchcraft during this time. Michael Bakewell, your slightly condescending host, sets up the narrative to follow in the opening sequence:

Are there really dangers involved or is it just a delusion? And if it is just a delusion why do some really quite intelligent people half believe in it?

Regardless of the producers’ skepticism, we still get to witness some magick on screen. One of the most valuable things captured in these films are footage and discussion of magical workings: Eleanor Bone’s coven’s working of a healing ritual for a close friend; Alex and Maxine Sanders — described as “well-known on television” — discuss their work on cancer cures with the aid of the spirit Michael; and an invocation of Diana performed by Doreen Valiente becomes the crux of questioning of the validity and perhaps, the sanity, of those involved in witchcraft. As Bakewell’s voice speaks over the footage, “Diana fails to appear” during the ritual.

In response, Valiente explains:

It was really difficult to get the spirit of the old ritual knowing you were surrounded by cameras and technicians and things like that. But when the ritual was almost at an end I began to feel the atmosphere building up and I think other people did too. This is what the ritual really means, it isn’t conjuring up a sort of pantomime demon or anything like that. It is something which affects your inner mind and works itself in your life and in your feeling and thought.

With that camera lens scrutinizing you, wouldn’t you look as fumbled as Valiente? While the producers may set her up for a small humiliation, she also gets to speak and stand her ground. This is the common theme in the film, as it juts back and forth between allowing witches and Pagans a space of legitimacy, and giving more power to the disbelieving voices of the common public.

The Legend of the Witches (1970)

Malcolm Leigh’s Legend of the Witches (1970) has been described by some as “The Citizen Kane of witchsploitation documentaries.”1 Yes, “witchsploitation” — a word used to described films created around this time which sought to cash in on the revival of witchcraft and the public’s growing interest in it.

Malcolm Leigh’s Legend of the Witches (1970) has been described by some as “The Citizen Kane of witchsploitation documentaries.”1 Yes, “witchsploitation” — a word used to described films created around this time which sought to cash in on the revival of witchcraft and the public’s growing interest in it.

However, it is — if you can stand the rather slow pace — a beautiful film shot in black and white with hard hitting compositions and an eerie feel that includes, at times, a good dose of psychedelia leftover from the prior decade. Probably meant to be shown in seedy public theatres for dirty old men looking for a thrill, the film is also a rather serious narrative piece which outlines (and depicts) the witches’ creation story, initiation rites, and the suppression of Paganism by Christianity.

After describing in detail the “doubtful” rites of historical Pagans, the narrator goes on to describe the “barbaric and repressive laws and ferocious tortures” practiced on them by the Christian church. The detailed account of the torture of a pregnant young woman is read aloud. A rather attractive actress with a rather large pregnant belly stands on a hill looking… well, attractive and pregnant. Hearing her torture read aloud is pretty traumatic and somewhat perverse, even if this dramatization is meant to be sympathetic.

Included are some really cool shots of Cornwall’s Museum of Witchcraft (now the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic). For those who’ve never had the chance to visit, let alone visit during the 1970s, the footage is a glimpse into the museum as it was at this time. The display cases and dioramas are dramatically lighted, while the rooms of the museum stay dark. We see ram horns a plenty, hand-written letters, and a display of poppets billed by the narrator as a “monument to hate,” among many other things.

The tension between pervy titillation and proper documentation is a fine line. Co-founders of Alexandrian witchcraft, Alex and Maxine Sanders, feature prominently in the film’s footage of ritual. But, let’s face it, there’s something pretty sexy about what they get up to and the Sanders were no strangers to the spotlight. They were also featured in other Pagan docs of the time: the even more scandalous, offensive, and, well, creatively shot, Witchcraft ’70 (1970) and Secret Rites (1971), both of which are shining examples of witchsploitation. Like Michael Bakewell said, the two were no strangers to television, and I would hope that they made some sort of an income in the process, alongside the perks of “promotion” in these films, if you’d call it that.

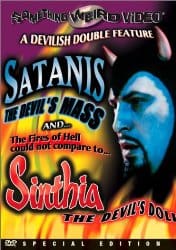

Satanis: The Devil’s Mass (1970)

Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, Ray Laurent’s documentary about Anton LaVey‘s Church of Satan is, of all the films on this list, the most objective. Laurent’s directorship seems incredibly involved, but at the same time, so very hands off.

Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, Ray Laurent’s documentary about Anton LaVey‘s Church of Satan is, of all the films on this list, the most objective. Laurent’s directorship seems incredibly involved, but at the same time, so very hands off.

Filmed inside the infamous Black House where the Church operated in San Francisco, we get a good hefty glimpse into the rituals and personalities of the organization, without the heavy voice over typical of some documentaries. LaVey and his congregation are given plenty of speaking time, both on their own and in groups, and their topics range from serious discussions of the beliefs of the church, to laughter filled conversations about the assumptions people make about them.

Neighbours of the Church are given screentime to air their grievances; an elderly man is disgusted with their behaviour and the upkeep of their lawn, and your friendly neighbourhood door to door Mormons are, of course, not impressed with the group’s politics. The people we hear from give us a range of responses, which really captures a complexity that I’m sure really existed, rather than a simple superficial one-sided narrative.

A woman who lives right next door lounges on a sofa with her child at her side — both are dressed in a marvellous shade of late ’60s coral — seems to have been charmed by LaVey’s good looks. She is also the source of a load of gossip about the Church, and regarding the guts it took Diane Hegarty to move in with the Satanist, she says “it takes a special type of young lady to marry a man with a lion.” Another young woman says she cannot condemn the Satanists for their beliefs and practices; that’s San Francisco for you, I guess.

What’s most interesting to me about this film is the “set”; while the Black House was torn down in 2001 to make room for a condo, in this film we’re given glimpses of its interior life in all its glory. Walls are painted pitch black, and adorned with LaVey’s collection of circus posters and paintings created by himself and others. He stands drinking liquor from a highball glass next to deep purple built in bookshelves. Surrounded by kind of kitschy occult memorabilia; skulls and charms which he describes as “memento moris.” I’m not sure if the cartoony ceramic devil on his cocktail bar counts, or not.

LaVey did one thing right while in the public eye, and that’s for sure. He, and his surroundings, were always dressed to kill.

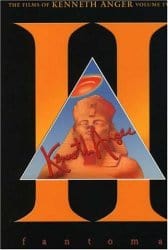

Honourable Mention: Kenneth Anger: Film as Magical Ritual (1970)

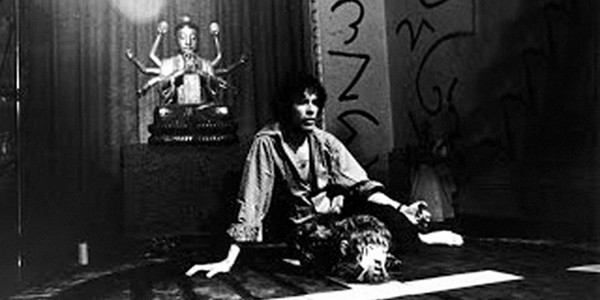

It was to my disappointment that the youtube file of Reinhold E. Thiel’s documentary, Kenneth Anger: Film as a Magical Ritual, had been placed under password protection, making it inaccessible when I finally got around to writing this piece. When I first watched it, I was blown away; it’s a piece made for German television that’s an inside look at the processes of the high priest of making magick on film, as he works on, of all things, Lucifer Rising.

It was to my disappointment that the youtube file of Reinhold E. Thiel’s documentary, Kenneth Anger: Film as a Magical Ritual, had been placed under password protection, making it inaccessible when I finally got around to writing this piece. When I first watched it, I was blown away; it’s a piece made for German television that’s an inside look at the processes of the high priest of making magick on film, as he works on, of all things, Lucifer Rising.

According to Dangerous Minds’ Richard Meztger,2 in the film:

Anger discusses his Aleister Crowley-inspired theories of art: How he views his camera like a wand and how he casts his films, preferring to consider his actors, not human beings but as elemental spirits. In fact, he reveals that he goes so far as to use astrology when making these choices.

This is as direct an explanation of Anger’s cinemagical modus operandi as I have ever heard him articulate anywhere. It’s a must see for anyone interested in his work and showcases the Magus of cinema at the very height of his artistic powers. Fascinating.

When faced with the question of whose really in charge, the answer is undeniably, Kenneth Anger. The fourth wall is broken down and we see the magick behind the camera. Hesitant about being filmed at all, he appears on his own terms; interviewed behind “a makeshift altar, lit in magenta and inside of the magical “war gods” circle seen at the end” of Lucifer Rising.

The magick is the message

Watching these films, what is the takeaway for occultists today? As I wrote up a short bio for an upcoming panel, Magick and the Occult in the Independent Arts at Canzine 2015, I tip-toed around the idea of naming my spiritual practice in the public eye. I’m about to get up and talk occultism with a community wider than I’ve ever dealt with before, and I’m nervous as hell. While I’m not on camera, I am certainly being watched, and undoubtedly, I’m being asked to perform.

As I — or even you — carefully craft some sort of public occult persona, attempting to strike the perfect balance between good publicity and honouring secrecy, it might be best to invoke Valiente’s smarts, the Sanders’ lack of camera shyness, LaVey’s style, and, of course, Anger’s magick.

- “Witchspoitation,” A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere [↩]

- “Film as Magical Ritual,” Dangerous Minds. [↩]