It’s not everyday that you get to see living history fill a room with fire.

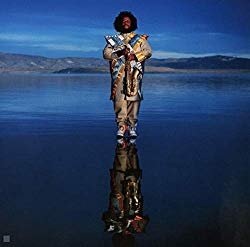

About a year ago, Pharoah Sanders (b. 1940) came to Arizona to play a pair of shows at the Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Scottsdale. The two shows filled up quickly, as for anyone with even a passing interest in jazz, this was a can’t-miss-event.

Sanders is a man with a deep connection to jazz history. He was rescued from homelessness by Sun Ra, and became a member of John Coltrane’s final quartet, and made his debut on Ascensions and went toe-to-toe with the big man on their tenor sax duel LP Meditations. He also added his signature sax sound to Alice Coltrane’s eastern jazz classic Journey in Satchidananda, and released a string of brilliant records under his own name. Albert Ayler, one of the gods of free jazz, declared that “Trane was the Father, Pharoah was the Son, I am the Holy Ghost.”

Part of the reason why seeing Sanders in the flesh is such a big deal is because he’s the only member of that Holy Trinity who’s left standing. Liver cancer took Coltrane, while Ayler was found dead in NYC’s East River. And most of the other jazz giants who joined Sanders on opening up this cosmic, unhinged vein of jazz have long since passed away as well: Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor… Perhaps the only other free jazz titan of Sanders’ stature left kicking is Anthony Braxton.

Pharoah Sanders at the Musical Instrument Museum, Scotsdale, Arizona

We had all come to the MIM to hear a living legend fill his lungs with fire and spirit. One last living link to a time when jazz mutated into something wild and occulted, when jazz cats tapped into the 60’s zeitgeist of LSD and astral explorations and went even further than the hippies. “Oh, that’s cute. You think that’s far out? Listen to this.”

When Sanders shuffled onstage, he seemed shrunken and diminutive. There was nothing about the way he carried himself that matched the regality of his name. But then he put his sax to his lips and grew to the size of Ra. He became the Sanders you hear on his astonishing half hour track “The Creator Has A Master Plan.” A man whose horn sounds like the sun slowly rising across the face of the Earth. A man who breathes fire and starlight. And that fire can turn volcanic. The back half of “Master Plan” sounds like all the beasts of the Earth waking up at the same time to howl and hoot at the sun. That night, we heard both sides of Sanders: fire and volcano, sunrise and screams.

But the moments I remember most about that night were those where he didn’t play anything at all. When his fingers flowed like liquid across his sax, hammering furiously on the bell keys, but no air came out. It was like he had been so completely possessed by the music that even when he wasn’t playing his instrument, his hands couldn’t help but dance along to the sound. It was like he was keeping his instrument warm and limber until the spirits came back and breathed through him again.

Related: Connected breathwork and subtle energy, by David Lee

Discovering occult music

When we think of music and the occult, we usually think of hippies and metalheads. Acid-licking white boys with hair down to their asses and horns thrown high in the air. But the truth is, if you had to pick one genre of music as being innately spiritual and magical, jazz is the most otherworldly form of music humans have created.

Anyone who doesn’t believe in the power of group-mind or telepathy hasn’t seen a dialed-in live ensemble at work. The way a handful of highly trained musicians can go completely off-script, hopping off the beaten path to explore No Man’s Land with improvised solos standing in for machetes, and not get lost. How they can make melodic discoveries and foresee where their partners are going — without one bit of verbal or written communication. Watching Sanders play with his band that night, you could feel them melding into the kind of “third mind” that William Burroughs and Brion Gysin used to talk about.

Related: Trancework in groups: Accessing mutual imagination, by Chrysanthemum White Alder

Deifying the greats

But there’s more to the spiritual qualities of jazz than the weird hive-minding that great jazz outfits achieve. God and otherworldly forces are frequently attributed in the music itself.

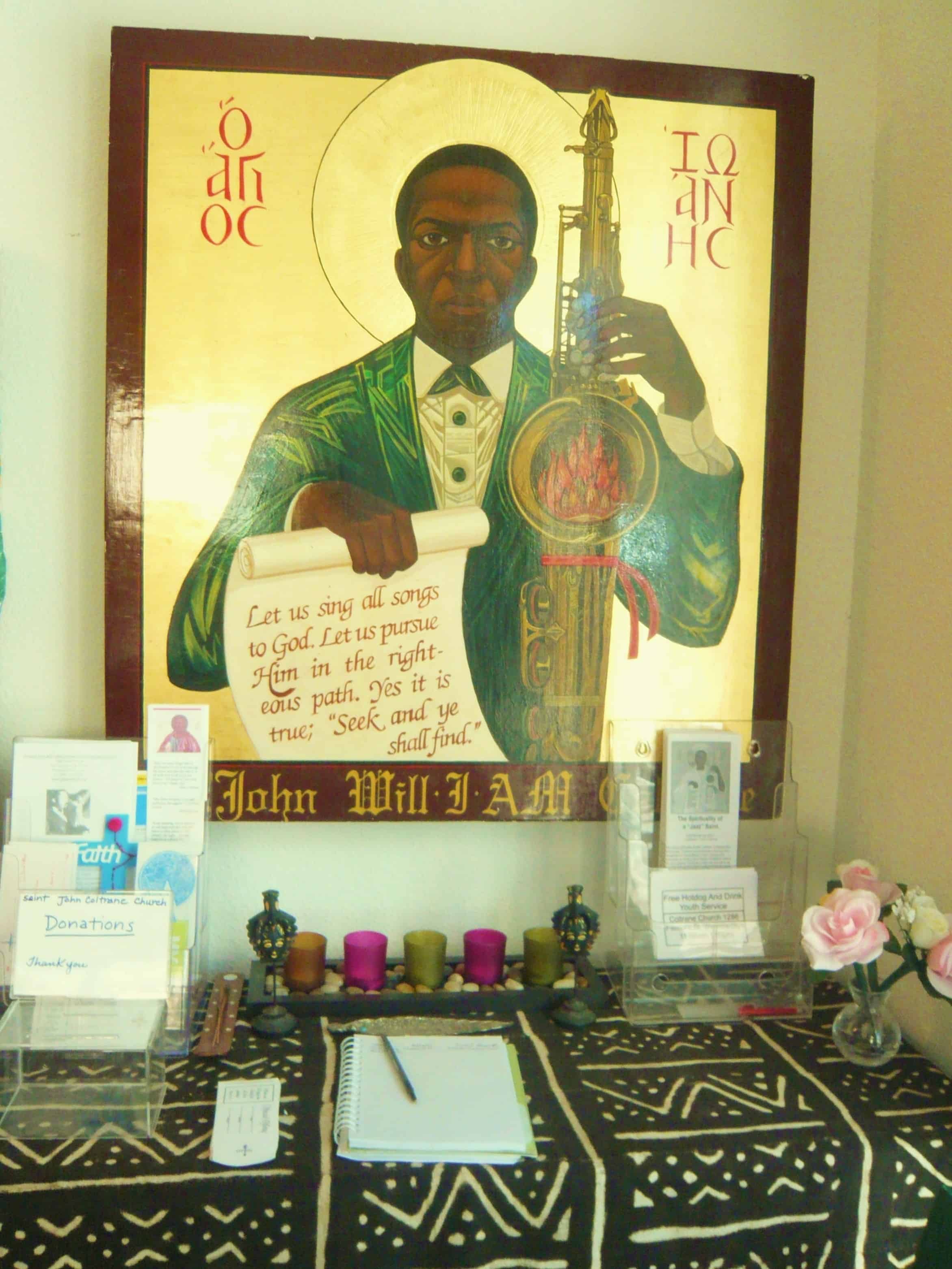

John Coltrane, a figure so deeply associated with jazz and spirituality that his example led to the founding of a church (the St. John Coltrane Church in San Francisco), believed that music itself had mystical potential — that certain sounds could elicit emotional and physical reactions from people.

Fascinated by world religions and Indian music, Coltrane devoted much of the back half of his catalogue to making music with a spiritual component. His 1965 masterpiece, A Love Supreme, was in many ways an ode to the Almighty. In the liner notes, Coltrane wrote that “I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.”

Coltrane also recorded his first record with Sanders in 1965. Ascension is a radical departure from A Love Supreme, a blast of elemental sound and fury. If A Love Supreme is the sound of someone floating blissfully through the cosmos, Ascension is someone drowning in it. It has the violent churn and ecstatic crescendos of someone undergoing a trance possession, like a Vodou dancer’s body being pushed to its limits by whatever lwa is riding it.

Related: African pantheons: A primer, by Donyae Coles

Spiritual influences

Other jazz legends were open about their spiritual obsessions. Fellow Coltrane and Sanders associate Albert Ayler talked about Creators and different dimensions on his records. On cuts like “Spirits Rejoice” and “Ghosts,” Ayler sounded like he was re-enacting the story of Jacob wrestling the angel with him and his sax standing in for the original fighters. In interviews and letters, he extolled the power of “meditation, dreams, and visions.” Bottom line: a person who calls their final album Music is the Healing Force of the Universe is going to believe in some woo-woo things.

And of course there’s the most woo-woo of them all: the mighty Sun Ra. Fuelled by a deep obsession with science fiction, Egyptology, and Freemasonry, Sun Ra became the godfather of Afrofuturism. He created a vision of jazz and music where the music makers looked and acted as far out as their sounds. In some ways, he was making explicit what was always present in jazz music: a deep yearning for escape, transcendence, communion with a higher reality.

There are also composers in other fields who’ve drawn inspiration from jazz’s spiritual explorations to inform their own work. John Zorn, whose work runs the gamut from free jazz to noise and klezmer music, has recorded entire albums about the Goetia, Aleister Crowley, and Thelema.

Not to mention that much of the excess of psychedelic music came from the influence of jazz. Consider how The Byrds drew on Trane’s example to create their psychedelic masterpiece “Eight Miles High,” or how jam bands like the Grateful Dead adopted the group-think mentality of jazz ensembles to make their marathon mushroom-fuelled improv jams possible.

Related: Alternative approaches to the Goetia, by Maria RavenSoul

Jazz’s spiritual influences spread

Punk music was also heavily informed by jazz. The godfathers of punk, The Stooges, were such huge jazz fans that they brought in Steve Mackay to blow his horn all over side two of Fun House. That potent fusion of garage rock nastiness and atonal horn-hooting would inspire a legion of punk and underground bands to add some sax to their lineup: X-Ray Spex, Essential Logic, Flipper, MX-80 Sound, Saccharine Trust.

Even metal has been touched by the ascending sound of jazz. The half hour to hour long song lengths that became commonplace on latter-day jazz recordings paved the way for metal groups to stretch out and record droning epics that would last for an entire album side. The wailing guitar noise and Cookie Monster vocals of metal has a lot in common with the dissonant howl of free-jazz: both genres use noise to articulate their relationship with the infinite. It’s the sound of tiny beings trying to fill the universe with their prayers and curses.

In a classic example of a broken clock being right at least twice a day, esoteric fascist Julius Evola nailed the occult appeal of jazz music in Ride The Tiger: “Jazz is undeniably an aspect of the resurfacing of the elemental in the modern world, bringing the bourgeois epoch to its dissolution.” He even picked up on jazz’s connection to Afro-Caribbean traditions like Vodou, how the music possessed an “ecstatic potential” like the dances initiates used to call down the spirits.

For a repugnant traditionalist and racist like Evola, these aspects were not selling points for jazz music. But he wasn’t wrong about the music’s potential to punch a hole in bourgeois society. Jazz’s evolution from “cool” bebop to wild, avant-garde free jazz made it unfit for popular consumption. You couldn’t have a “nice” dinner party while listening to Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come. Musicians like Alice Coltrane and Ayler raving about the benefits of Eastern mysticism and Om chants and altered states of being put them closer in spirit to the unwashed Age of Aquarius hippies that were scandalizing the nation. Like Christian moms in the ’80s ringing their hands over the corrupting influence of heavy metal, Evola saw the revolutionary appeal of this kind of music. And just like those moms, it scared the shit out of him.

It’s also why this cosmic, magical strain of jazz music is oddly absent from Ken Burns’ 19-hour long documentary series on jazz music. The boundary pushing, mindfucking innovations of later-period Coltrane, Ayler, Sanders, Coleman, Braxton, and the rest of the free jazz scene get reduced to a footnote in Ken Burns’ Jazz. And why is that? Because they threaten our modern conception of jazz as polite, whitebread, elevator music. Music that is orderly and predictable and pleasant, that doesn’t make you reach for earplugs. It’s why everybody loves Kind of Blue Miles and not On the Corner Davis: the former is magnificent wallpaper and the latter makes a scene.

Related: Ride the Tiger, reviewed by Susan Starr

Jazz ascends

Jazz has been having a resurgence over the last few years, thanks in large part to the crossover appeal of Kamasi Washington’s work. You can hear him on Kendrick Lamar records, connecting Kendrick’s Compton rap roots to an older musical tradition (much in the same way that Ron Carter’s nimble bass playing on Low End Theory built a bridge in time between bebop and A Tribe Called Quest’s Zulu Nation hip-hop).

Musical innovators like Thundercat and Flying Lotus (grand-nephew to Alice Coltrane) also tap into the cosmic drugginess of jazz. It isn’t just that they sample and re-contextualize the sounds of jazz and funk and integrate them into modern electronic productions and rap — they also embrace the spiritual obsessions that powered that music. Both Thundercat and Lotus have recorded entire albums about the soul’s descent into the afterworld and have made trippy, hallucinatory music videos. Like their jazz inspirations, they haven’t forgotten that this kind of music is head music — the kind of shit you should be banging while flying high on DMT or doing ritual work in a dark basement.

While Washington hasn’t been quite as vocal as Trane of Ayler on spiritual matters, it’s hard not to listen to albums like Heaven and Earth and The Epic without thinking about astral projecting, Om mantras, and heavenly ascensions. They’re albums that sounded rooted in “the eternal now” and the past, fusing modern R&B sounds with the kind of interstellar noodling and volcanic sax eruptions that his forefathers made sound as easy as breathing.

Related: How to achieve altered states of consciousness, by Jarred Triskelion

The way forward

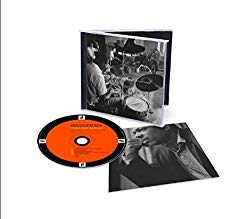

Both Washington and Coltrane have released new albums this summer. Washington’s Heaven and Earth points the way forward. Like Ornette before him, Washington is laying down the sound of jazz to come. As for Coltrane: the long-dead master lives again with the release of Both Directions at Once. A “lost album,” it’s culled from tapes of recording sessions Coltrane did with his classic quartet in 1963.

This is just a few years before Trane and company issued their gorgeous hymn to the Eternal in A Love Supreme and shot out into hyperspace on Ascension. But you can already hear the group evolving in these twin directions: they make music that’s as lovely and conventional as their older work, but you can also hear violent rumbling in Elvin Jones’ drumming and Coltrane’s horn strains and pushes toward something bigger than itself. They haven’t quite hit their out of body phase yet, but there are moments where their bodies go slack and some ghostly limbs reach out of them, hoping to grab the bottom rung to a ladder leading them Upstairs.

Related: Into the Mystic, reviewed by Alanna Wright

Music to send you to the Eternal

Image credits: ReflectedSerendipity, Wikimedia Commons, Markus, danisabella, Toshiyuki IMAI, dancekevin, Young Turks,