Trance Dancing with the Jinn: The Ancient Art of Contacting Spirits Through Ecstatic Dance, by Yasmin Henkesh

Trance Dancing with the Jinn: The Ancient Art of Contacting Spirits Through Ecstatic Dance, by Yasmin Henkesh

Llewellyn Worldwide, 978-0738737942, 408 pp., 2016

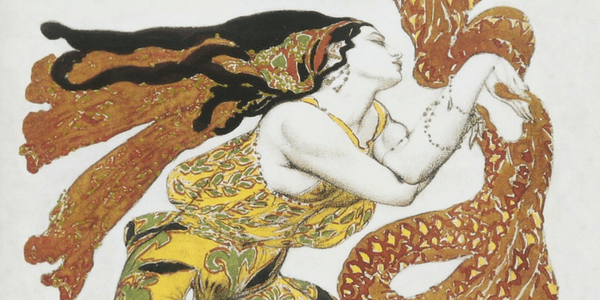

The first section of Trance Dancing with the Jinn focuses on trance: its definition, history, experience, and science. Kinetic trance like this, she notes, is good “for people who hate to sit still.”1 I found the history of specific movements very intriguing. For instance, Henkesh discusses the traditional “horned cow” arm position of Hathor‘s dancers in ancient Egypt, which later was modified to imitate Hathor’s hieroglyphic symbol — rounded arms pointing skyward around Ra‘s solar disc. It is now a standard arm position for belly dancers, somewhat similar to ballet’s fifth position, I might add.2 Throughout the book there are a large number of illustrations to help the reader understand the dance positions being discussed.

Flow: being pushed by the music like air pushes a flame, curving hips like a flame curved by a breeze… I draw fire into my dance and breathe on it to make the candle flame my dance partner….

That is an excerpt from my journal entry for Yasmin Henkesh‘s “Dancing with Fire” exercise in Trance Dancing with the Jinn. I have practiced a form of light trance dancing for many years — improvisation with a goal of finding flow, usually beginning with belly dancing moves then expanding to include movements I have learned in a wide variety of dance classes and movements I discover in the moment. Henkesh’s “trance dance manual” added a new spark to my autodidactic practice.

Henkesh’s grasp of history is broad, including fascinating examples like the Paleolithic Venus, the Great Mother of Catal Hoyuk, Cybele’s orgiastic rituals, and the Maenads in Euripides’ “Bacchae.” (The latter was also excerpted in several dance poetry anthologies that I’ve recently read.) The history chapter is occasionally a little too broad for my tastes, such as the timeline that reaches back to 3.3 million BCE and includes many details about human evolution to argue for the origins of trance dancing in East Africa’s Middle Paleolithic period.3

However, I enjoyed Henkesh’s first-hand descriptions of a zar hadra in Cairo — a weekly female trance dance ritual of spirit possession — and the discussions of how trance dance is used in trauma therapy.4 Henkesh does not attempt to teach spirit possession, but focuses on ways to induce flow, enter the objective observer stage where “theta flares”5 can inspire creativity, and finally achieve the disembodied soul stage of descent into trance.6 Her discussions of how dizziness plays a role in inducing trance made me reconsider how I unconsciously hold my breath when approaching and entering a state of flow. I used to try to remind myself to breathe, but reading Trance Dancing with the Jinn made me think that I may be able to use this instinctive breath-holding, or other forms of breath control, to enter deeper stages of trance.

The second section of the book is about contacting spirits in the form of djinn, or “Invisibles.” Henkesh considers this practice the “holy grail of trance dancing,” usually only achievable through dedication and desire.7 A glossary of various types of djinn is compiled from the Qur’an and Edward Lane’s Account of the Manners and Customs of Modern Egyptians. Details about these Invisibles also come from the Book of Jinn, a medieval manuscript entitled Akaam al-Murjaan fi Ahkaam al-Jaan.8 One homework assignment also recommends reading djinn stories from the Arabian Nights translations by Lane and Richard Burton.

Henkesh notes that before the “codification of Islam, the jinn were fiery nature spirits” from different parts of Africa9 and called zars. Zar can refer to both spirit and the trance dance ritual which originated in Ethiopia,10 and is seen in Sudan, Nigeria, and Yoruba. Like their predecessors, Egyptian zars are predominately female trance dance rituals, and include women of all ages. Islamic culture in Egypt, Henkesh argues, places many restrictions on women. For instance, their marriages are often arranged, and can be polygynous, and their movements are limited. However, possession during trance dance allows for otherwise unpermitted hedonism and freedom. A woman is allowed to drink, smoke, and refuse sex from her husband when “married” to a djinn, “in the name of pleasing her possessor.”11

Possession aside, zars give women the opportunity to leave their houses and spend time with other women. Like most forms of exercise, trance dancing produces serotonin, which can help combat melancholic depression and other forms of stress caused by poverty and patriarchical culture.12 Personally, I have discovered that even light trance dance states, such as finding improvisational flow, are therapeutic in my struggles with poverty, depression, and anxiety.

Women’s zars are contrasted with traditionally masculine zikrs, including Rumi‘s famous Mevlevi Sufi whirling and the popular modern shaabi zikrs, which are attended by both men and women. Sufi whirling, Henkensh explains, is about channeling Allah directly13 rather than dealing with the much lesser — and often maligned — djinn spirits that are sought in zars. The zikr’s traditional form is highly choreographed, unlike the more improvisational zars. Popular shaabi zikr dancers also perform a wider variety of solo movements (like club dancing), which are detailed in the third part of the book.

The third and final part of Trance Dancing with the Jinn focuses on kinetic dance techniques. Henkesh’s practical guide for trance induction includes how to prepare, warm up, zikr, zar, whirl, and cool down. She includes a number of modifications, lists contraindicated conditions (such as epilepsy and migraines), and pictures of herself posed for the movements. As someone who is prone to headaches and occasional migraines, I quickly discovered that some of the hair-flinging and head-banging zar movements are not a good induction method for me. It’s too bad because they would look cool with my waist-length hair — albeit not as impressive as with the author’s knee-length locks!

However, some of the movements were familiar, and did not result in a terrible headache, and I tried modified versions of them in my trance dancing. For example, the zar sway, also called Weaving 8s, is like a much larger version of some figure 8 movements I have done in belly dance, and the shaabi zikr twists remind me of a “palm tree” pose I have done in yoga classes. Henkesh explains that the goal of most movements is to agitate the inner ear fluid,14 and includes advice on how to safely fall from dizziness or descent into trance, which is similar to what I was taught in modern dance classes that have choreographed falls.

I highly recommend Trance Dancing with the Jinn for experienced dancers, especially belly dancers and ravers. Henkesh’s explanations are clear and detailed enough for many novice dancers, but some beginners might struggle without video or in-person instruction. Considering that only one section of the book — less than a third of the text — is practical dance instruction, I also recommend Trance Dancing for lovers of dance and trance history.

- p. 13 [↩]

- p. 30 [↩]

- p. 58 [↩]

- For example, Terpsichore Trance Therapy. [↩]

- In her Trance Science chapter, Henkesh describes the different brainwave frequencies: gamma, beta, alpha, theta, and delta. Theta (4-8 Hz) is the frequency that automatically occurs right before and in light stages of sleep, and can be produced intentionally in deep meditation. Waking theta indicates “altered consciousness” that unlocks “your subconscious door,” producing inspiration, psychic feelings, and emotional recall. [p. 94-95] [↩]

- p. 79-81 [↩]

- p. 116-117 [↩]

- p. 157 [↩]

- p. 173 [↩]

- p. 204 [↩]

- p. 188-189 [↩]

- p. 188-189 [↩]

- p. 225 [↩]

- p. 265 [↩]